Christian Mythology

Christian folklore is the assortment of legends related with Christianity. The term includes a wide assortment of legends and stories, particularly those thought about sacrosanct stories. Legendary subjects and components happen all through Christian writing, including repeating fantasies, for example, climbing to a mountain, the pivot mundi, legends of battle, drop into the Hidden world, records of a withering and-rising god, a flood fantasy, tales about the establishing of a clan or city, and legends about extraordinary legends (or holy people) of the past, heavens, and benevolence.

Different creators have likewise utilized it to allude to other legendary and figurative components tracked down in the Good book, like the account of the Leviathan. The term has been applied to fantasies and legends from the Medieval times, like the account of Holy person George and the Mythical serpent, the narratives of Ruler Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, and the legends of the Parsival. Numerous observers have characterized John Milton's legendary sonnet Heaven Lost as a work of Christian folklore. The term has additionally been applied to present day stories spinning around Christian subjects and themes, like the works of C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Madeleine L'Engle, and George MacDonald.

Throughout the long term, Christianity has separated into numerous groups. Not these groups hold similar arrangement of hallowed conventional stories. For instance, the books of the Holy book acknowledged by the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Standard houses of worship incorporate various texts and stories (like those described in the Book of Judith and Book of Tobit) that numerous Protestant categories don't acknowledge as sanctioned.

Contents

Perspectives

See moreover: Religion and folklore

Christian scholar and teacher of New Confirmation, Rudolf Bultmann composed that:[1]

The cosmology of the New Confirmation is basically legendary in character. The world is seen as a three celebrated structure, with the earth in the middle, the paradise above, and the hidden world underneath. Paradise is the habitation of God and of divine creatures - the heavenly messengers. The hidden world is heck, the spot of torture. Indeed, even the earth is more than the location of normal, ordinary occasions, of the trifling round and normal assignment. It is the location of the heavenly action of God and his holy messengers from one perspective, and of Satan and his devils on the other. These extraordinary powers mediate over nature and in all that men think and will and do. Supernatural occurrences are in no way, shape or form uncommon. Man isn't in charge of his own life. Malicious spirits might claim him. Satan might rouse him with malicious contemplations. On the other hand, God might move his thinking and guide his motivations. He might allow him brilliant dreams. He might permit him to hear his assertion of aid or interest. He might provide him with the otherworldly force of his Soul. History doesn't follow a smooth solid course; it is gotten rolling and constrained by these otherworldly powers. This æon is held in servitude by Satan, sin, and demise (for "powers" is exactly what they are), and rushes towards its end. That end will come very soon, and will appear as an infinite fiasco. It will be initiated by the "troubles" of the last time. Then, at that point, the Appointed authority will come from paradise, the dead will rise, the last judgment will happen, and men will go into everlasting salvation or condemnation.

Legends as customary or hallowed stories

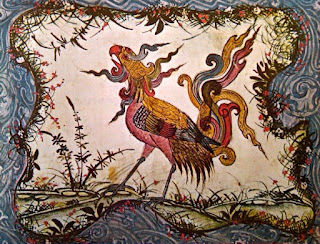

Holy person Brendan's journey, from a German original copy

In its broadest scholastic sense, the word fantasy basically implies a conventional story. In any case, numerous researchers confine the expression "fantasy" to sacrosanct stories.[2] Folklorists frequently go further, characterizing legends as "stories accepted as evident, typically holy, set in the far off past or different universes or regions of the planet, and with extra-human, barbaric, or courageous characters".[3]

In old style Greek, muthos, from which the English word legend determines, signified "story, account." When of Christ, muthos had begun to assume the implications of "tale, fiction,"[4] and early Christian essayists frequently tried not to consider a story from sanctioned sacred text a "myth".[5] Paul cautioned Timothy to not have anything to do with "heathen and senseless fantasies" (bebēthous kai graōdeis muthous).[6] This negative importance of "fantasy" passed into famous usage.[7] A few present day Christian researchers and journalists have endeavored to restore the expression "legend" outside scholarly world, portraying stories in standard sacred text (particularly the Christ story) as "genuine fantasy"; models incorporate C. S. Lewis and Andrew Greeley.[n 1] A few present day Christian journalists, like C.S. Lewis, have depicted components of Christianity, especially the tale of Christ, as "fantasy" which is too "valid" ("genuine myth").[8][9][10] Others object to partner Christianity with "legend" for different reasons: the relationship of the expression "fantasy" with polytheism,[11][12][13] the utilization of the expression "legend" to demonstrate misrepresentation or non-historicity,[11][12][14][15][16] and the absence of a settled upon meaning of "myth".[11][12][16] As instances of Scriptural fantasies, Each refer to the creation account in Beginning 1 and 2 and the narrative of Eve's temptation.[17]

Christian custom contains numerous accounts that don't come from standard Christian texts yet still show Christian topics. These non-accepted Christian fantasies incorporate legends, folktales, and elaborations on standard Christian folklore. Christian custom has created a rich collection of legends that were never integrated into the authority sacred writings. Legends were a staple of middle age literature.[18] Models incorporate hagiographies like the tales of Holy person George or Holy person Valentine. A valid example is the verifiable and sanctified Brendan of Clonfort, a sixth century Irish churchman and organizer behind monasteries. Round his real figure was woven a tissue that is seemingly unbelievable as opposed to verifiable: the Navigatio or "Excursion of Brendan". The legend talks about mythic occasions in the feeling of extraordinary experiences. In this story, Brendan and his shipmates experience ocean beasts, a paradisal island and a drifting ice island and a stone island occupied by a heavenly loner: exacting disapproved devotés still try to recognize "Brendan's islands" in genuine geology. This journey was reproduced by Tim Severin, proposing that whales, chunks of ice and Rockall were encountered.[19]

Folktales structure a significant piece of non-sanctioned Christian custom. Folklorists characterize folktales (rather than "valid" legends) as stories that are viewed as simply made up by their tellers and that frequently miss the mark on unambiguous setting in space or time.[20] Christian-themed folktales have flowed broadly among worker populaces. One far and wide folktale sort is that of the Humble Miscreant (named Type 756A, B, C, in the Aarne-Thompson list of story types); one more well known gathering of folktales depict a sharp human who outsmarts the Devil.[21] Not all researchers acknowledge the folkloristic show of applying the expressions "legend" and "folktale" to various classifications of customary narrative.[22]

Christian custom created numerous well known stories expounding on standard sacred text. As indicated by an English society conviction, certain spices acquired their ongoing mending power from having been utilized to recuperate Christ's injuries on Mount Calvary. For this situation, a non-sanctioned story has an association with a non-account type of fables — in particular, people medicine.[23] Arthurian legend contains numerous elaborations upon standard folklore. For instance, Sir Balin finds the Spear of Longinus, which had pierced the side of Christ.[24] As per a practice broadly confirmed in early Christian works, Adam's skull lay covered at Calvary; when Christ was killed, his blood fell over Adam's skull, representing mankind's reclamation from Adam's sin.[25]

Comments

Post a Comment